The Second Anglo-Powhatan War erupted with devastating ferocity on March 22, 1622. After eight years of relative peace between the English colonists and the Powhatan Chiefdom in Virginia, Powhatan leaders like Opechancanough (Chief Powhatan’s brother) orchestrated a deadly surprise attack on settlements along the James River.

Article by Henricus Historical Park Staff

1622-1632-Virginia: Second Anglo-Powhatan War

This attack sparked a decade long war that shifted the balance of power towards the English and further diminished Powhatan authority. As the longest and perhaps most important of the three Anglo-Powhatan Wars, this conflict fueled massive changes with wide-reaching effects for the history of colonial America.

The English and Powhatan had a history of conflict dating back to the founding of Jamestown that intensified during the First Anglo-Powhatan War (1609-1614). After five years of bitter fighting, the marriage of Pocahontas to John Rolfe ushered in a peace that provided the English a stronger foothold in Virginia. The years after 1614 saw rapid colonial expansion as more and more settlers spread out across the countryside to grow tobacco—the main cash crop of the fledgling colony. As the English presence grew, settlers took valuable hunting and gathering grounds away from the Powhatan, and they became more brazen in their treatment of the natives. Whether in displacing them from their land, openly insulting their culture, or treating them like a conquered people within their own territory, the English displayed an arrogance that enraged many Powhatans, especially leaders like Opechancanough. In Opechancanough’s eyes, it was time to teach the English newcomers a lesson.

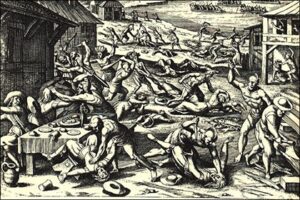

Recalling the lethality of English arms from previous encounters, Opechancanough believed in the necessity of surprise. He subsequently planned his assault with great secrecy and lulled the English into a false sense of security before the fateful day. On March 22, 1622, large numbers of Powhatan people came unarmed to trade with colonists across many upriver settlements. Easily gaining entrance into settler’s houses and towns, they then turned on them in a coordinated attack using the English’s own tools and weapons to strike. Over 300 people or about a third of the colony perished on that day, and more would die in the coming months. The remaining colonists, recoiling in fear, retreated to more heavily defended fortifications near Jamestown and on the Eastern Shore. Despite his success in chastising the English and clearing out many upriver plantations, however, Opechancanough did not follow up his victory and move to destroy the English—likely because he never intended to do so. Instead, he succeeded in his limited aims of contracting the radius of English settlements and reminding them of Powhatan supremacy. The English did not see it that way though, and their retreat to forts was only temporary while they reorganized and awaited fresh troops.

in chastising the English and clearing out many upriver plantations, however, Opechancanough did not follow up his victory and move to destroy the English—likely because he never intended to do so. Instead, he succeeded in his limited aims of contracting the radius of English settlements and reminding them of Powhatan supremacy. The English did not see it that way though, and their retreat to forts was only temporary while they reorganized and awaited fresh troops.

The English eventually counterattacked through a series of raids intended to ruin Powhatan harvests, which eventually culminated in the only major battle of the war in 1624 when English soldiers defeated Pamunkey warriors in a battle lasting two days. For the rest of the war, the English continued their strategy of leading lightning raids through the heart of the Powhatan chiefdom and drawing on their large population back home to supplement their forces. By 1632 when a peace treaty was finally signed, Powhatan power was greatly reduced, and the English were able to expand even further.

Ultimately, the Second Anglo-Powhatan War had long-reaching effects. For one, the war helped facilitate the fall of the Virginia Company and the implementation of royal rule by 1624—a move with big effects on the future of the colony. The war also contributed to a hardening of English attitudes towards the Powhatan. Opechancanough’s assault convinced many Englishmen of the Indians’ supposed perfidy, and it allowed the colonists to justify a vicious war of removal. Indeed, the conflict reignited the brutality that had marked the first war with tactics centered around the destruction of settlements, foodstuffs, and populations. This model of warfare would be used with deadly effect by successive generations of English and British troops across North America. Furthermore, the new policies of removal of Indian populations (rather than assimilation) implemented in the aftermath of 1622 would go on to inform British and American ideas about Native Americans for centuries to come.

with big effects on the future of the colony. The war also contributed to a hardening of English attitudes towards the Powhatan. Opechancanough’s assault convinced many Englishmen of the Indians’ supposed perfidy, and it allowed the colonists to justify a vicious war of removal. Indeed, the conflict reignited the brutality that had marked the first war with tactics centered around the destruction of settlements, foodstuffs, and populations. This model of warfare would be used with deadly effect by successive generations of English and British troops across North America. Furthermore, the new policies of removal of Indian populations (rather than assimilation) implemented in the aftermath of 1622 would go on to inform British and American ideas about Native Americans for centuries to come.