In March of 1661, the Virginia General Assembly passed laws concerning the ownership of enslaved peoples as well as the theft of indentured servants.

Article by Henricus Historical Park Staff

Slavery had no legal basis in the colony of Virginia nor any real precedent in the English system when the first recorded Africans arrived in Virginia in 1619. It instead took decades for the practice of racialized, chattel slavery to become standardized and officially legalized by the Virginia General Assembly in 1661. While 1661 marks the codification of the practice, previous legislation and court decisions in the colony laid much of the groundwork by beginning to restrict Black freedoms and making race into a legal distinction. Slavery and its accompanying ideological and racial apparatus grew exponentially after its legalization in Virginia, eventually becoming the primary labor system of Virginia and the rest of the South (and legal in all thirteen colonies on the eve of the American Revolution).

Slavery did not develop in Virginia overnight, and for much of the seventeenth century, indentured servitude was the primary labor system of the colony. Already practiced in England, servitude seemed a natural choice for Virginia. Indentured servants primarily came from the lower orders of society and could not afford the passage overseas, so they agreed to work without pay for a set number of years (typically four to seven) in return for their transport. Most white colonists in the half-century after Jamestown’s founding arrived as indentured servants, and some Africans transported to Virginia were also employed as such.

Slavery did not develop in Virginia overnight, and for much of the seventeenth century, indentured servitude was the primary labor system of the colony. Already practiced in England, servitude seemed a natural choice for Virginia. Indentured servants primarily came from the lower orders of society and could not afford the passage overseas, so they agreed to work without pay for a set number of years (typically four to seven) in return for their transport. Most white colonists in the half-century after Jamestown’s founding arrived as indentured servants, and some Africans transported to Virginia were also employed as such.

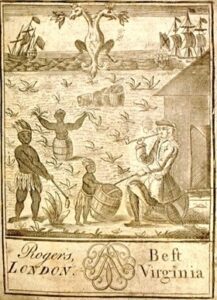

Demographic changes, examples from abroad, and the need to control labor eventually brought about changes in the status of Africans and slavery in Virginia. For much of the early seventeenth century, the African population of the colony stayed quite tiny, but their numbers began to steadily increase around mid-century as more English merchants tapped into the wealth generated by the African slave trade. This demographic shift coupled with the rising cost of indentured laborers led many Virginia planters to slowly replace white indentures with Black slaves. Drawing on similar labor shifts seen in English Caribbean colonies like Barbados, Virginia planters (the same men capable of serving in the colonial legislature and courts) strengthened their legal hold over this labor force. They passed new laws and sent down legal decisions that differentiated treatment and freedoms based on race, codifying the system of slavery and legalizing it by 1661.

The 1661 legalization of slavery was just the beginning, however. Throughout the remainder of slavery’s legal existence in the colony, the General Assembly regularly added statutes to strengthen the system by increasing the power of slaveholders and restricting the rights of slaves and Black people. The next decade witnessed a series of laws that did just that. For instance, a 1667 law withdrew a previous prohibition on enslaving Christians, closing an avenue of freedom for slaves in Virginia. Similarly, a 1669 law allowed slaveholders to punish their slaves and escape without legal repercussions if they accidentally killed them in the process. Further events in Virginia, such as the social chaos engendered by Bacon’s Rebellion and the economic upheaval of the late seventeenth century, helped entrench the system. By 1705, the General Assembly enacted the colony’s first comprehensive slave codes—reissuing and bringing together several earlier laws—making Virginia’s transition to slavery largely complete.

The 1661 legalization of slavery was just the beginning, however. Throughout the remainder of slavery’s legal existence in the colony, the General Assembly regularly added statutes to strengthen the system by increasing the power of slaveholders and restricting the rights of slaves and Black people. The next decade witnessed a series of laws that did just that. For instance, a 1667 law withdrew a previous prohibition on enslaving Christians, closing an avenue of freedom for slaves in Virginia. Similarly, a 1669 law allowed slaveholders to punish their slaves and escape without legal repercussions if they accidentally killed them in the process. Further events in Virginia, such as the social chaos engendered by Bacon’s Rebellion and the economic upheaval of the late seventeenth century, helped entrench the system. By 1705, the General Assembly enacted the colony’s first comprehensive slave codes—reissuing and bringing together several earlier laws—making Virginia’s transition to slavery largely complete.