“Built on the Hill called Indian Town”:

St. John’s Church from Inception to the Second Virginia Convention

It was October 12, 1740, and William Byrd II had a problem. A wealthy landowner and progenitor of the Byrd dynasty in Virginia, he had offered property to the Henrico Parish Vestry (the parish’s governing board) for building a new church, and the Vestry had accepted. The land, “near ye Spring on Richardsons Road, on the South Side of Bacon’s Branch,” was the second proposed location, the Vestry having first independently selected land on “Thomas Williamsons plantation on the Brook Road.” But, to Byrd’s dismay, he discovered that access to the new church would require a mile of roadway, ruining his plans for other development of his property. So, Byrd wrote to the Vestry with a counteroffer: an acre of land in the new town of Richmond on “two of the best Lots. . . and any pine timber they can find on that side of Shockoe Creek, and Wood for burning of the Bricks into the Bargain.”

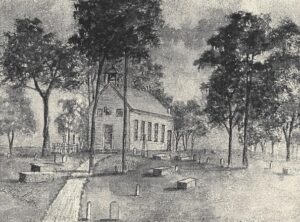

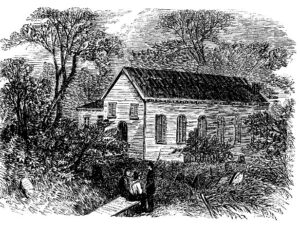

The following day, the Vestry voted on whether to accept Byrd’s counteroffer or build the new church at the original location on the Brook Road, resulting in the former winning by a majority of the ten Vestrymen in attendance. Thus, the new church would be “built on the Hill cal(l)ed Indian Town” in Richmond. The builder would be Richard Randolph, a member of the Vestry, owner of Curl’s Plantation, and through marriage a direct descendant of Pocohontas. Randolph also had built the Parish’s existing place of worship, Curl’s Church, eponymously named for its location. The new church would be a simple structure, “Sixty feet Long and Twenty-five broad And fourteen feet pitch’d, to be finished in a plain manner.” The construction price was set at 317 pounds and ten shillings.

The Vestry records do not specify the actual date of completion and do not document any delays in construction. The church was probably completed by or near the contract date of June 10, 1741, a date approximately supported through recent dendrochronological analysis. The Vestry held its first meeting at Richmond on November 13, 1749, although worship services likely began in 1741. Lacking a formal name, the church was variously referred to as the “New Church,” “Upper Church,” “Town Church,” “Richmond Church,” and the “Church on Richmond Hill.” (The name St. John’s would not be used until 1829, a creation of the rector at that time, Reverend William Lee.)

Shortly after the church was completed, the property became a burial ground for church members and religious leaders. The oldest known interment is John Coles, a native of England who arrived in Virginia in 1730 at the age of twenty-five. A successful merchant, he amassed considerable wealth, assisted William Byrd II in laying out the city of Richmond and purchased large tracts of land from him. He owned several plantations and property and was a member of the vestry at the time of his death in 1747. During repairs in 1987, workers discovered under the chancel a brass plate with the name John Coles, evidence of his burial at that location.

The oldest visible burial is that of Robert Rose. Born at Wester Alves in Scotland, Reverend Rose was ordained by the Bishop of London and immigrated to colonial Virginia about 1728. He explored Nelson County and received land grants in Virginia from the English royal government. He patented 23,700 acres along the Piney and Tye Rivers in Nelson County. His first church was St. Anne’s in Essex County, where he served from 1726 to 1748. He became rector of Albemarle Parish in 1749, serving until his death in 1751 on his way to Richmond, where he was to consult on laying out the city.

As the new city of Richmond continued to grow, so did the Church membership. By the early 1770s, the Vestry saw a need to expand the building. At a meeting on December 8, 1772, the Vestry authorized “An addition of Forty feet in Length and of the same width (twenty-five feet) as the pres’t Church at Richmond is (to) be built to it, at the North Side with a Gallery on both Sides & one End the proper windows above and below.” The Vestry specified that “lowest bidder” perform the work. The surviving records do not record who constructed the addition nor its cost, but it appears to have been completed within the next year or so. The 1772 addition expanded the Church by two-thirds, making it the largest building in Richmond—and the location for an important meeting that would occur less than three years later.

In May 1774, the British royal governor of colonial Virginia, Lord Dunmore,

effectively dissolved the colony’s legislative body, the House of Burgesses. Dunmore and his representatives were concerned about the growing resistance to and resentment of British authority and governance. Shortly thereafter, the burgesses met at the Raleigh Tavern in Williamsburg. They agreed not to import any British goods, passed a resolution encouraging all colonies to send delegates to an upcoming Continental Congress in Philadelphia, and scheduled another meeting in Williamsburg for August 1774—the First Virginia Convention. At the August convention, delegates elected Payton Randolph, Speaker of the House of Burgesses, as president. They agreed to stop British imports and exports and to postpone payments owed by Virginia colonists to British creditors. The delegates also selected seven members to represent Virginia at the upcoming Continental Congress in Philadelphia.

As relations between the colonies and Great Britain continued to deteriorate, delegates held the Second Virginia Convention in March 1775. With Williamsburg vulnerable to attack, St. John’s Church in Richmond was selected since it was a day or more of travel by horseback from the colonial capital. Importantly, the church was one of the few buildings in Virginia large enough to accommodate the approximately 120 delegates. In addition, the church’s minister, Miles Selden, was sympathetic to the purpose of the convention.

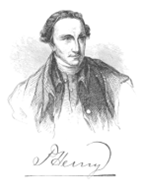

Attendees at the convention included George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Payton Randolph, Richard Henry Lee, Richard Bland, Archibald Cary, Edmund Pendelton, Geroge Mason, Benjamin Harrison, and Patrick Henry. The delegates unanimously elected Randolph as president. Randolph had also been president of the Continental Congress and led discussions about that meeting. During the first three days of the convention, the delegates approved the decisions made by the congress in Philadelphia and conducted other business.

On the fourth day, March 23, 1775, Patrick Henry rose to speak. Henry, who a few months earlier had confided to friends that he believed war with Great Britain was inevitable, made three resolutions:

- “that a well-regulated militia. . . is the natural strength and only security of a free Government” and would render unnecessary the need for a British military force,

- “that the establishment of such a militia is. . . necessary. . . for the protection and defense of the Country,” and

- “Resolved therefore that this Colony be immediately put into a posture of defense” and that a committee be appointed to plan and make ready an army.

Henry spoke with enthusiasm and conviction, aware that many in attendance would find his resolutions premature and even provocative. He concluded his address to the convention with some of the most famous words in American history:

Why stand we here idle? . . . Is life so dear and peace so sweet as to be purchased at the price of chains and slavery? Forbid it, almighty God! I know not what course others may take; but as for me, give me liberty or give me death!

A contentious debate followed Henry’s impassioned speech. But his argument was a powerful one, and the delegates approved his resolutions, although narrowly. The written record of the convention does not specify the exact vote, but reportedly of the approximately 118 delegates in attendance on March 23, 1775, 60 to 65 voted in favor of the resolutions. Henry’s war premonition was correct. Less than a month after his speech, the American Revolution began in Massachusetts with the Battles of Lexington and Concord.

The Churchyard is the final resting place for twenty-three veterans of the American Revolution. Among these is George Wythe, a signer of the Declaration of Independence. Wythe was a law professor at the College of William and Mary and taught John Marshall, James Monroe, Henry Clay, and Thomas Jefferson. He was also a clerk at the Virginia House of Burgesses, speaker of the House of Delegates, judge of the Virginia Chancery, and a delegate to the Federal Constitutional Convention. He died in 1806, after drinking coffee that had been poisoned with arsenic by his nephew.

Two Revolutionary era Virginia governors are interred in the Churchyard. John Wood was the 11th Governor of Virginia, serving from 1796 to 1799. He served with George Washington in the French and Indian War and was a member of the House of Burgesses. During the American Revolution he was a colonel in the 12th Virginia Regiment and later in the 8th Regiment. He was a leading member of the Abolition Society of Virginia. John Page was the Governor of Virginia from 1802 to 1805. He served in the French and Indian War and in the American Revolution as a colonel in the Gloucester County militia where he fought in the Battle of Yorktown. After the Revolution, Page was elected to the Virginia House of Delegates and later to the United States Congress, serving from 1789 to 1797. He fathered twenty children with his two wives.

Other noteworthy Revolutionary War veterans include Richmond physicians James Currie, William McClurg, and William Carter. Under an agreement with the British forces, Dr. Carter wore an identifying red cloak allowing him to treat both British and American soldiers. William Randolph was a lieutenant in the Continental Navy. A prominent merchant and businessperson, he owned the Eagle Tavern in Richmond. Edward Carrington, an attorney who held many important state and federal government positions, is interred near one of the windows on the east side of the church. He reportedly was listening to Henry’s March 1775 speech just outside the east window of the church and stated that he was so moved by the oration that he wanted to be buried on the spot where he was standing.